Translate this page into:

Anxiety Levels of Doctors Working in Kolkata during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study

CITATION: Banerjee A, Paul B, Dasgupta A, Bhattacharyya M, Bandyopadhyay L, Ghosh P. Anxiety Levels of Doctors Working in Kolkata during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study. J Comp Health. 2021;9(1):23-31.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Ankush Banerjee, All India Institute of Hygiene & Public Health 110, Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata-700073. E Mail ID: ankush.baneriee20@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

Abstract

Background:

Doctors are amongst the major frontline healthcare providers combating the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic situation. This overwhelming burden has not only resulted in physical exhaustion but also taken a toll on their mental health. This study thusaimed to determine the anxiety levels among doctors working in Kolkata and identify its associated factors if any.

Methodology:

This cross-sectional study was done through an online social media platform from August to October 2020, in Kolkata among 313 doctors selected by volunteer sampling. Levels of anxiety were assessed by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (modified for COVID-19 pandemic). Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis was done to elicit factors associated with high anxiety levels among them.

Results:

Among 313 study participants,31.9% had mild, 22% moderate and 6.4% had severe anxiety levels. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that younger age [AOR=1.15, 95%CI=1.04-1.25], female gender [AOR=3.25, 95%CI=1.02-10.31], working in government sector [AOR=4.78, 95%CI=1.45-15.69], presence of associated co-morbidity [AOR=37.67, 95%CI=8.01-177.11], working as designated frontline COVID-19 healthcare worker [AOR=4.57, 95%CI=1.04-20.12], working in increasing number of high-risk areas [AOR=1.81, 95%CI=1.09-3.00], perceived poor quality of available PPE [AOR=12.26, 95%CI=3.86-38.95] and increasing number of difficulties faced while working at the health facility [AOR=3.67, 95%CI=2.30-5.84] had significant association with high anxiety levels.

Conclusion:

Present study showed that a considerable proportion (28.4%) of doctors had high anxiety levels. Maintaining appropriate COVID-19 protocols at the workplace, periodic health check-up to detect co-morbidity at the earliest, counselling services with particular attention to female providers would add to the betterment of their mental health.

Keywords

Anxiety Levels

Doctors

Kolkata

COVID-19 Pandemic

INTRODUCTION

Tracing its origin to the Chinese city of Wuhan, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has emerged as a worldwide public health crisis affecting 218 countries.[1] India is among the top 5 countries affected by this ongoing pandemic with a confirmed case-load exceeding 14 million.[2,3]

The ever-increasing number of cases as well as the multi-sectoral impact of the pandemic has created a huge panic among the general population. In addition to the above difficulties, medical professionals especially frontline workers are overburdened with increased workload due to which physical exhaustion & mental fatigue is also setting in gradually. Studies across the globe have cited numerous reasons for their poor mental health status such as increased workload, perceived high risk of contractinginfection from confirmed or suspected cases, inadequate protection, lack of experience, perceived stigma from their family members or neighbours, significant lifestyle changes, living in quarantine facilities and also fear of transmission of the disease to their families and colleagues.[4,5,6]

Previous studies in Toronto[7] and Hong Kong[8] during the previous epidemic of SARS(2002) as well as recent studies during the ongoing pandemic phase in China, Oman, Turkey and Pakistan have shown increased levels of mental stress and anxiety among healthcare personnel.[9,10,11,12]

In India, although studies have been done assessing the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population[13,14], few studies have been conducted till date assessing its impact on the mental well-being of healthcare providers.[15,16,17] A study is yet to be conducted in West Bengal thus necessitating further research in this domain especially in the context of eastern India. This study thus envisaged assessing the anxiety levels of doctors working in Kolkata during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and elicit its associated factors’ if any. The findings would serve as a piece of important evidence to direct the initiatives to be taken at the policy level for improving the promotion of mental well-being among medical professionals.

MATERIAL & METHODS

Study Design and Study Period

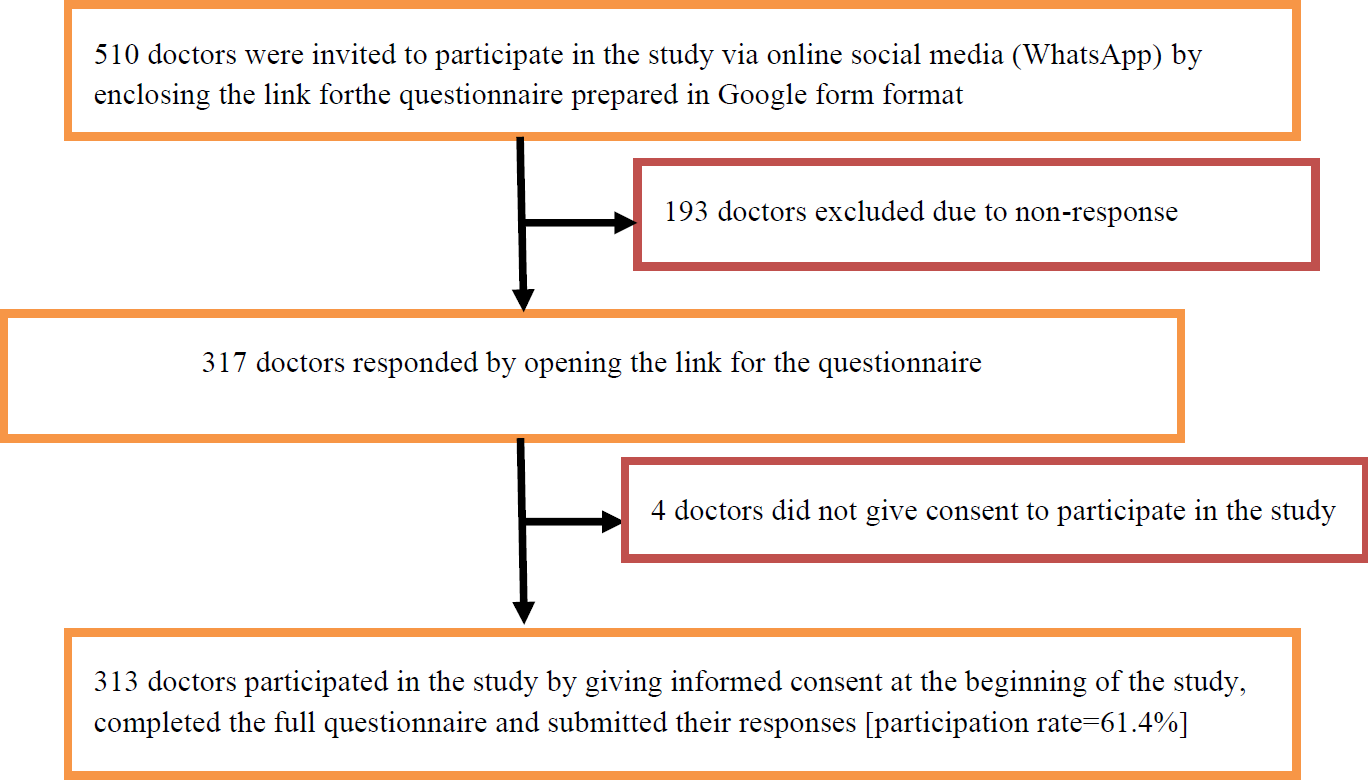

This cross-sectional study was conducted from August to October 2020 through an online social media platform to minimize face to face interaction and facilitate the participation of doctors without borrowing much of their valuable working time during this pandemic phase.

Study population

The study participants consisted of 313 doctors working in different healthcare facilities across Kolkata during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and having access to online social media. Participants who did not give written informed consent & those who did not reply within the specified time frame were excluded from the study.

Sampling

A previous study done during the ongoing pandemic by AlAteeq et al in Saudi Arabia[18] reported a prevalence of high anxiety levels among healthcare workers to be 26.3%. Considering P= 0.263 and absolute error of precision=5%, the minimum sample size estimated using standard Cochran's formula came to be 298.[19] Participants were selected by volunteer sampling technique.

Study technique

A questionnaire was created in Google form format and the link for opening the form was generated which was distributed among the study participants with the help of social media. At the beginning, participants were requested to provide informed consent to participate in the online survey, only after which they could fill the whole questionnaire by self-reporting. After full completion, participants had to submit the questionnaire to get their responses recorded. To prevent duplication of the responses, participants had to log in with their email login credentials and thus could submit the questionnaire with his/her responses only once. (Figure 01)

- FLOW-DIAGRAM SHOWING METHOD OF RECRUITMENT OF THE STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Study tools and parameters used

The study tool consisted of a pre-designed pre-tested structured self-reported questionnaire which collected data across the following domains:

Socio-demographic characteristics and clinical profile of the participants included age, gender, educational qualification and associated co-morbid medical conditions with health.

Working Place characteristics included the type of working health-care facility, working experience (in years), whether working in high-risk areas in the health facility [The five high-risk areas considered were fever clinic, general infectious disease wards including COVID-19 wards, Intensive Care Units, Emergency Units and Pathology/Microbiology/Biochemistry laboratories. Based on working in these high-risk areas, a total score was calculated ranging from ‘0’ (Not working in any of the above high-risk areas) to a possible maximum of ‘5’ (working in all the mentioned 5 high-risk areas) with working in each high-risk area being given a score of ‘1’], number of working hours per week, whether working as a designated frontline COVID-19 healthcare worker and type of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) available at their healthcare facility along with its perceived quality and quantity.

Change in professional activity post-emergence of the pandemic was assessed by a 7-item questionnaire denoting the presence or absence of 7 mentioned difficulties while working in their healthcare facilities. (Table 01) The presence of each item had a score of "1” and its absence was denoted as "0”. The total score was calculated by adding the scores of the individual items. Thus, a study participant could have a maximum score of "7” (faced all the 7 difficulties) and a minimum of "0” (faced no difficulties).

Anxiety levels of the participants were assessed using the GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7) scale modified to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic situation. It consisted of a 7-item questionnaire comprising symptoms used for screening anxiety in clinical practice. Pre-testing was done among 30 doctors in a different setting via an online platform who were not included in the study. The reliability of the scale was checked by Cronbach's alpha (=0.82) and via inter-item correlation. Face and construct validity were checked by public health experts and no significant change in internal validity was found compared to the original scale. Participants were asked how many times in the past 2 weeks they experienced the mentioned symptoms. The responses were recorded in the form of "Not at all”, "Several days”, "More than half the days” and "Nearly every day” and subsequent scores were given as 0,1,2 and 3 respectively. (Table 02) Total score of all the 7 items thus ranged from 0-21. Cut-off points of 5, 10, and 15 were interpreted as representing mild, moderate, and severe anxiety levels.[20] The diagnostic threshold was previously reported to be 10.[21] Therefore, total scores ranging from 10-21 were reported as having "High anxiety” (moderate to severe anxiety) levels.

| Parameters | Yes n (%) | No n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Faced difficulty while doing clinical examination and maintaining social distancing | 225(71.9%) | 88(28.1%) |

| Had difficulty while consulting through telemedicine | 210(67.1%) | 103(32.9%) |

| Found difficulty in following proper sanitization measures after examining each patient in the healthcare facility | 236(75.5%) | 77(24.5%) |

| There has been an increase in workload during the past few months after the emergence of the pandemic | 237(75.7%) | 76(24.3%) |

| Faced difficulty while collecting swabs or testing samples in the laboratories | 212(67.7%) | 101(32.3%) |

| Had difficulty living in quarantine facilities | 214(68.4%) | 99(31.6%) |

| Felt exhausted while working for long hours with the thick PPE donned. | 221(70.6%) | 92(29.4%) |

| Parameters | Not at all n (%) | Several days n (%) | More than half the days n (%) | Nearly everyday n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being nervous or anxious while coming in contact with a confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infected patient | 39(12.5%) | 162(51.8%) | 71(22.7%) | 41(13%) |

| Being unable to stop worrying about contracting the COVID-19 infection and spreading it to others | 51(16.3%) | 147(47%) | 73(23.3%) | 42(13.4%) |

| Being too much worried about you & your family members getting stigmatized by neighbours | 94(30%) | 117(37.4%) | 48(15.3%) | 54(17.3%) |

| Having difficulties in relaxing after hearing news of some known person getting infected with COVID- 19 | 126(40.3%) | 155(49.5%) | 14(4.5%) | 18(5.7%) |

| Being agitated and unable to stay still after viewing news of the rampant spread of COVID-19 on electronic and social media | 189(60.4%) | 85(27.2%) | 33(10.5%) | 6(1.9%) |

| Getting easily irritated in simple matters | 182(58.3%) | 84(26.7%) | 37(11.8%) | 10(3.2%) |

| Having fear that some terrible things may happen (death or financial losses) if you or your family members become very sick after contracting the COVID-19 infection | 44(14.1%) | 158(50.5%) | 67(21.3%) | 44(14.1%) |

Statistical data analysis

All statistical data analysis was done with the help of Microsoft Excel (2016) & Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (IBM Corp. version 16). Continuous variables were described by Mean± Standard deviation (SD) or Median with Interquartile Range (IQR) whereas categorical variables were described as numbers with percentages. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was estimated to rule out multicollinearity among the variables (VIF>10). Factors associated with high anxiety levels were seen by a test of significance (p-value<0.05) at 95% confidence interval in a Logistic Regression model.

Ethical issues

Permission from the institutional ethics committee was obtained before beginning the study. Participants were requested to give written informed consent before participating in the study. They were assured that their identity will not be disclosed and data provided by them will be kept confidential.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Clinical Profile of the study participants

Among the 313 study participants, the median age was 35 years (IQR=28-41). Males (49.2%) formed a similar proportion as compared to female participants (50.8%). Among all the participants, 19.8% were interns, 15.7% were junior residents, 20.7% were resident medical officers, 17.6% were senior residents and 26.2% of the participants were consultants including teaching faculty. Among the 63 (20.1%) participants who had one or more co-morbid medical condition associated with their health, 49 participants had only one co-morbid condition whereas 14 participants had two co-morbid conditions associated with their health.

Cardiovascular disease was the most common medical condition (present among 55.2% of participants having associated co-morbidities with their health) followed by diabetes (41%)

Proportion of anxiety levels among the study participants

The total anxiety scores obtained were not normally distributed and thus denoted by a median value of 6 (IQR: 4-10). Among all the study participants, 100(31.9%) had mild anxiety, 69(22%) had moderate anxiety and 20(6.4%) had severe anxiety levels. Thus 89(28.4%) participants had high (moderate-severe) anxiety levels. (Figure 2)

![DISTRIBUTION OF THE ANXIETY LEVELS OF THE STUDY PARTICIPANTS [N=313]](/content/169/2021/9/1/img/JCH-9-023-g002.png)

- DISTRIBUTION OF THE ANXIETY LEVELS OF THE STUDY PARTICIPANTS [N=313]

Working place Characteristics of the study participants

There was an almost similar proportion of doctors working in the government and private sector. Working experience (in years) of the study participants had a median value of 8 (IQR=2-13) Doctors working as designated front-line COVID-19 worker constituted 63.9% of the study participants. Among 224 participants who were working in one or more high-risk areas, 45.9% were working in fever clinic, 32.1% in general infectious disease wards (including COVID-19 wards), 33.4% in intensive care units, 43.8% in emergency units and 17.8% in Pathology/ Microbiology/ Biochemistry laboratories. In the high-risk area domain, a maximum score of 4 was obtained (working in 4 high-risk areas) and a minimum of 0. Therefore, the total score in this domain had a median value of 1 (IQR=0-2) PPE was available in all the health facilities in the form of sterile disposable surgical masks (available to 96.8% of all participants), sterile disposable gloves (91.6%), N-95 respirator masks (77.5%), disposable gowns with boots (69.3%) and face-shield with goggles (45%).

Change in Professional activity post-emergence of the pandemic

Among 313 study participants, 19.8% did not face any of the mentioned 7-difficultieswhile working at their healthcare facility, while the rest 80.2% faced one or more of the above difficulties. The total score obtained in this domain had a median value of 2(IQR=1-3). The most common difficulties faced by the study participants were increased workload after emergence of the pandemic (75.7%) and following proper sanitization measures (75.5%) while 70.6% of the participants felt exhausted after working for long hours with the thick PPE donned. (Table 01)

Factors associated with high anxiety levels

Univariate logistic regression analysis estimated the unadjusted odds ratio which showed a significant association between high anxiety levels among the participants with several factors. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that younger age [AOR=1.15, 95%CI=1.04-1.25], female gender [AOR=3.25, 95%CI=1.02-10.31], working in government sector [AOR=4.78, 95%CI=1.45-15.69], presence of associated co-morbid medical condition [AOR=37.67, 95%CI=8.01-177.11], working as designated frontline COVID-19 healthcare worker [AOR=4.57, 95%CI=1.04- 20.12], working in increasing number of high-risk areas in the healthcare facility [AOR=1.81, 95%CI=1.09-3.00], perceived poor quality of available PPE [AOR=12.26, 95%CI=3.86-38.95] and increasing number of difficulties faced while working at the healthcare facility [AOR=3.67, 95%CI=2.30-5.84] had a significant association with high anxiety levels. Since age and working experience were found to have high multicollinearity (VIF=16.2), only age was included in the final multivariable model. The non-significant Hosmer-Lemeshow test (0.215) indicated good fitness of the final multivariable model, while 56-75% of the variance of high anxiety level could be explained by the model. [Cox & Snell R[2]=0.563, Nagelkerke R[2]=0.752]. (Table 03)

| Parameters | Total number N | High(moderate-severe) anxiety levels n (%) | Unadjusted OR † (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR † (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreasing Age (in years) * | 1.18(1.12-1.23) | <0.001 | 1.15(1.04-1.25) | 0.005 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 154 | 26(16.9%) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||

| Female | 159 | 63(39.6%) | 3.23(1.90-5.47) | <0.001 | 3.25(1.02-10.31) | 0.045 |

| Educational Qualification | ||||||

| Graduate (MBBS) | 174 | 69(39.7%) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||

| Post-graduate & above (MD/MS/Dnb/DM/MCh) | 139 | 20(14.4%) | 0.256(0.14-0.45) | <0.001 | 0.96(0.26-3.48) | 0.957 |

| Increasing Working Experience (in years) * | 0.835(0.78-0.88) | <0.001 | — | — | ||

| Type of Health facility | ||||||

| Government Sector | 152 | 68(44.7%) | 5.39(3.08-9.44) | <0.001 | 4.78(1.45-15.69) | 0.010 |

| Private Sector | 161 | 21(13%) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||

| Usual working hours/week | ||||||

| 24-36hrs/wk. | 169 | 30(17.8%) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||

| 36-48hrs/wk. | 107 | 42(39.3%) | 2.99(1.72-5.20) | <0.001 | 1.55(0.42-5.69) | 0.508 |

| >48hrs/wk. | 37 | 17(45.9%) | 3.93(1.84-8.40) | <0.001 | 1.04(0.16-6.45) | 0.962 |

| Working as designated frontline COVID-19 health care worker | ||||||

| No | 113 | 17(15%) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||

| Yes | 200 | 72(36%) | 3.17(1.75-5.73) | <0.001 | 4.57(1.04-20.12) | 0.044 |

| Co-morbid medication condition associated with health status | ||||||

| Absent | 250 | 41(16.4%) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||

| Present | 63 | 48(76.2%) | 16.31(8.35- 31.86) | <0.001 | 37.67(8.01- 177.11) | <0.001 |

| Working in increasing number of high-risk areas* | 2.07(1.61-2.62) | <0.001 | 1.81(1.09-3.00) | 0.022 | ||

| Perceived quality of PPE available at the health facility | ||||||

| Good | 202 | 29(14.4%) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||

| Poor | 111 | 60(54.1%) | 7.01(4.08-12.07) | <0.001 | 12.26(3.86- 38.95) | <0.001 |

| Perceived quantity of PPE available at the health facility | ||||||

| Adequate | 239 | 49(20.5%) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||

| Inadequate | 74 | 40(54.1%) | 4.56(2.62-7.94) | 2.21(0.68-7.18) | 0.186 | |

| Increasing number of difficulties faced while working thus affecting professional activity* | 2.42(1.96-3.00) | <0.001 | 3.67(2.30-5.84) | <0.001 | ||

*CONTINUOUS VARIABLES, † OR= ODDS RATIO, CI=CONFIDENCE INTERVAL

DISCUSSION

This study was done to address the impact of the pandemic on the mental health & well-being of doctors who are working tediously during this ongoing pandemic.

A considerable proportion of doctors (28.4%) was found to have high anxiety levels. A previous study in Oman, by Badahdah et al done during the ongoing pandemic, utilized the GAD- 7 scale & found a similar proportion (25.09%) of healthcare workers suffering from high anxiety levels.[10] A recent study done in India by Gupta et al found 35.02% of doctors suffering from high anxiety levels.[22] This considerable proportion of high anxiety levels among doctors in Kolkata is a great alarming sign and risk factors for such high anxiety levels should be properly addressed and adequate measures need to be taken to reduce their psychological burden.

Studies done in India by Suryavanshi et al[15] and Gupta et al[23] have demonstrated that younger age being significantly associated with high anxiety levels among healthcare workers. The results of our study have also shown this similar association as decreasing age of the study participants were found to be significantly associated with high anxiety levels.

Studies done previously in Pakistan[12] and China[24] during the ongoing pandemic have shown female healthcare workers having significantly higher odds of suffering from high anxiety levels. Both these studies had high female preponderance among the study participants in comparison to males. In contrast, our study had an almost similar proportion of males and female participants but still found a similar association of female gender with high anxiety levels.

Doctors working in the government sector showed significantly higher chances of suffering from high anxiety as compared to their colleagues working in the private sector which was found similar to the study conducted in Maharashtra, India by Suryavanshietal.[15] Government healthcare facilities in India have a huge burden of patient and workload which may have contributed to the development of high anxiety levels among medical professionals. A recent study in China by Liu et al demonstrated frontline cOvID-19 healthcare workers having significantly higher odds of suffering from high anxiety levels.[9] Our study also found similar results to this study as 36% of designated front-line doctors showed high anxiety levels.

Our results showed that 76.2% of doctors who had one or more associated co-morbid conditions had high anxiety levels compared to a paltry 16% of those with no associated co-morbidities. According to data provided by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, more than 70% of all deaths due to COVID-19 in India were associated with co-morbidities.[3] This information might have had a serious impact on the mental well-being of doctors having co-morbid conditions which in turnmay have led to development of high anxiety among them.

PPE forms a vital component of doctors as it serves as a protective shield for our ‘COVID-19 warriors’. Participants who perceived that the PPE available to them was of poor quality had significantly higher odds of high anxiety levels than those having access to good quality PPE. Although a significant association of perceived inadequate PPE availability with higher anxiety levels was noted in the univariate logistic regression model, no such significant association was noted in the final multivariable model. Therefore, the supply of good quality and adequate quantity of PPE should be given prime importance by the administrative authorities. Lack of proper protection will in turn lead to mental stress thus compromising the working capacity of an individual.

This study elicited the most common difficulties faced by doctors working in different healthcare facilities of Kolkata post-emergence of the pandemic which has significantly altered their professional activity. High anxiety levels were noted among participants facing increasing number of difficulties& this association was found to be statistically significant. Significant lifestyle changes and difficulties faced while consulting patients along with a conducive working environment can seriously impair the mental health status and working capability of our ‘COVID-19 warriors’ and suitable interventions can help in improving this situation.

Strengths

A unique attempt was made by modifying the GAD-7 scale to make it pertinent for the ongoing pandemic. The symptoms of anxiety in the questionnaire were modified to determine the anxiety levels of the participants primarily due to the emergence of this ongoing pandemic situation.

Limitations

The study is limited by its cross-sectional nature and lacks longitudinal follow-up, so the causal association between the different factors and the anxiety levels could not be established. Since this study was conducted through an online social media platform & participants were selected through volunteer sampling, this might have led to a selection bias and the respondents may not have full representation of the entire population. Also, bias due to self-reporting of the study participants may be present

Conclusion

The present study showed a considerable proportion (28.4%) of doctors working in Kolkata during this ongoing COVID-19 pandemic having high anxiety levels and also elicited its important associated risk factors. Doctors are one of the major frontline warriors who are combating this pandemic situation. Therefore, it is essential to take care of not only their physical health but also their psychological well-being so that they can perform to their full potential. Maintaining appropriate COVID-19 protocols at the workplace, periodic health check-up to detect co-morbidity at the earliest, counselling services with particular attention to female healthcare providers would add on to the betterment of their mental health. All these strategies can be implemented at the policy level so that we can improve the mental well-being of our medical professionals so that they can keep working to their full potential for combating not only this ongoing pandemic but also against any subsequent pandemics in future.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTION

All the authors contributed equally.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants who took time from their busy schedule to fill the questionnaire and participate in the study.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization 2020 Rolling updates on coronavirus disease. [Internet] Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel- coronavirus-2019/events-as-they happen [last cited on 16th April 2021]

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus resource center: COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns HopkinsUniversity (JHU) Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Last cited on (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Government of India [Internet] Available from: www.mohfw.gov.in [last cited on (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):e14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:127-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(3):e100259.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: lessons learned. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1117-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of severe respiratory syndrome on anxiety levels of front-line health care workers. Hong Kong Med J. 20041;0(5):325-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID- 19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e98.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The mental health of health care workers in Oman during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020 Jul 8 20764020939596

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290 113130

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety among Doctors during COVID-19 Pandemic in Secondary and Tertiary Care Hospitals. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;6(6):1360-1365.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Depression, Anxiety and Stress Among Indians in Times of Covid-19 Lockdown. Community Ment Health J 2020 Jun 23:1-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depression, anxiety, and stress and socio-demographic correlates among general Indian public during COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;6(8):756-762.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health and quality of life among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Brain Behav. 2020;10(11):e01837.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID- 19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559-565.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in India: An observational study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(12):5921-5926.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health among healthcare providers during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2020;3(10):1432-1437.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essential of Biostatistics & Research Methodology. (3rd). Academic Publishers; 2020. p. :86-114. Pages:

- [Google Scholar]

- A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;4Med Care. 2008;6(3):266-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Health Among Armed Forces Doctors During COVID-19 Pandemic in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(4):374-378.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Survey of prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among 1124 healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic across India. Med J Armed Forces India 2020 Sep 1

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(3):e203976.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]