Translate this page into:

Health Inequalities in India - Will Looking through The Social Determinants Lens, Make A Difference?

Corresponding Author: Dr CS Taklikar, Professor Department of Health Promotion and Education, All India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health, Kolkata Email: shekhartaklikar@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Dobe M, Taklikar C S. Health Inequalities in India - Will Looking through The Social Determinants Lens, Make A Difference? J Comprehensive Health 2019;7(2): 6-11.

Why treat people ... then send them back to the conditions that made them sick?

In other words, what good will universal health coverage be, if we cannot change the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age (the social determinants) These conditions are, in turn, shaped by political, social, and economic forces resulting in differences in health that are closely linked with social disadvantages, most of which are avoidable /preventable through well designed and implemented policies and programs.1

These avoidable inequalities within and between societies which determine their risk of illness and the actions taken to prevent them becoming ill or treat illness when it occurs are termed Health inequities. From time immemorial public health has tried to look into differences in numbers (prevalence/incidence) in different socioeconomic positions and revealed that, health and illness follow a social gradient- the lower the socioeconomic position, the worse the health. 1

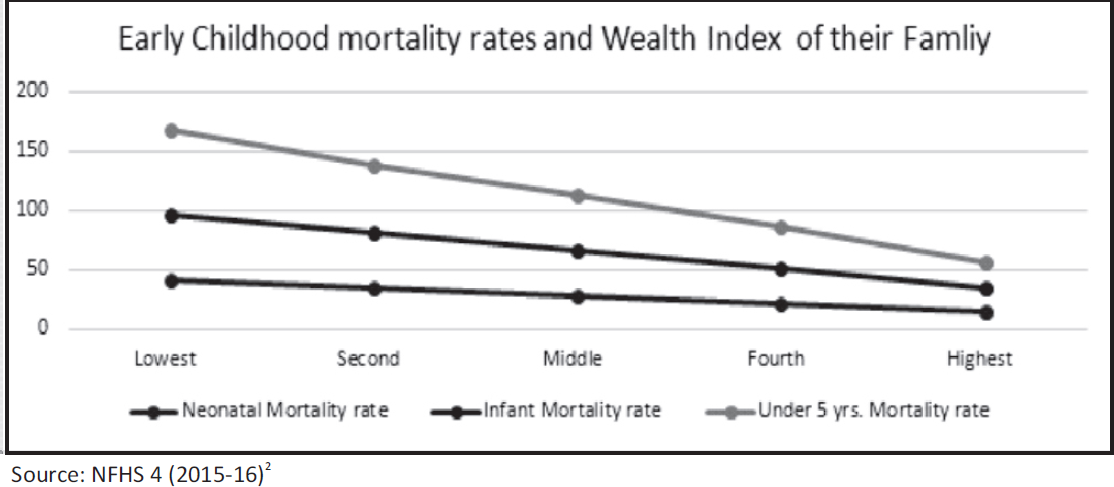

For example, if we look at under-5 mortality rates by levels of household wealth we see that within our country the relation between socioeconomic level and health is graded. The poorest have the highest under-5 mortality rates, and people in the second highest quintile of household wealth have higher mortality in their offspring than those in the highest quintile.

However, majority of people in the world do not enjoy the good health that is biologically possible, due to the influence of social determinants operating across policies, economics, and politics (WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health)3

That this is not only the case in low and middle- income countries, it is as much true in the high-income countries and even there, gross disparities exist within countries as is evident from the data given below:

Although traditionally, society expects the health sector to address its concerns about health and disease, the high burden of illness and premature loss of life arises largely because of the social determinants, operating as impact of public policies and programs in other sectors as well.

- Early childhood mortality rates and Wealth Index of their Family

| Country | Life Expectancy at Birth (Male) |

|---|---|

| Glasgow, Scotland (deprived suburb) | 54 |

| India | 61 |

| Philippines | 65 |

| Korea | 65 |

| Lithuania | 66 |

| Poland | 71 |

| Mexico | 72 |

| Cuba | 75 |

| US | 75 |

| UK | 76 |

| Glasgow, Scotland (affluent suburb) | 82 |

Source:(WHO World Health Report 2006; Hanlon,P.,Walsh,D. & Whyte,B.,2006)

At this juncture, despite multitude of programs and policies designed to promote health of the population, India still faces the challenges of addressing health inequities - the solution lies in looking through multilevel social epidemiological lens.

While social factors affecting health are mentioned in a majority of public health studies and gradually being considered in Public Health Programs, in India, these are still viewed more as statistical covariates and not as influencing factors. However, the lack of significant progress in prevention of disease, as well as the persistence of socio-economic inequalities in health, emphasizes the need for a paradigm shift in public health policies and interventions by incorporating a social determinants and life course perspective for looking into factors ranging from policies to community-level resources and addressing the cumulative effect of inequalities through generations.1

This will enable identification of pathways linking these factors from macro to micro levels, opening up possible areas for intervention.

Let us raise a few queries:

Is the existing distribution of health care designed in concerned policies and programs delivering care to those who need it most? Maternal mortality/morbidity and reproductive health services remain hugely inequitably distributed within the country e.g. the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) (130 per 100000 live births) in India ranged between 237 in Assam to 46 in Kerala. Gradually the realization has evolved that maternal and reproductive health is a social phenomenon as much as a medical event, where access to and use of maternal and reproductive health care services are influenced by contextual factors.1 A systematic review4 on inequity in maternal health in India highlighted the fact that women of some population groups remained systematically and consistently disadvantaged in terms of access to and use of maternal and reproductive health services, including safe delivery and antenatal care services.

The key observations from the Bottleneck Analysis5 (for national level), carried out using specific indicators for each intervention and latest data sources are: 1. Limited availability of skilled human resources, especially nurses. 2. Low coverage of services and of skilled staff posting among marginalized communities. 3. Inadequate supportive supervision of front-line service providers. 4. Low quality of training and skill building. 5. Lack of focus on improving quality of services. 6. Insufficient information, education and communication on key family practices.

How then should we relook into these gaps?

Can the health system itself be considered an indirect determinant of health inequities? Benzeval, Judge and Whitehead6 argue that the health system has three obligations in confronting inequity: (1) to ensure that resources are distributed between areas in proportion to their relative needs; (2) to respond appropriately to the health care needs of different social groups; and (3) to take the lead in encouraging a wider and more strategic approach to developing healthy public policies at both the national and local level, to promote equity in health and social justice.On this point the UK Department of Health has argued that the health system should play a more active role in reducing health inequalities, not only by providing equitable access to health care services but also by putting in place public health programmes and by involving other policy bodies to improve the health of disadvantaged communities

In the decade since it was launched, Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), a government-run conditional cash transfer program launched in 2005-06 to persuade women to deliver their babies in institutional setting, has significantly improved the rate of institutional deliveries among rural women.A nine- state analysis of the effects of JSY7 reveals that while inequality in access to care has reduced dramatically. The percentage of institutional births in India has doubled from 38.7% to 78.9% in the decade to 2015-16, according to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4)1 there still remains a gap in accessing hospital-based delivery. The analysis reveals that nearly 70 percent of this could be attributed to differences in male literacy, disparities in access to emergency obstetric care and high levels of poverty, unfolding newer / finer dimensions of social injustice/ inequalities.

Similarly, in their study on "Evaluation of the Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram: findings on inequity in access from Chhattisgarh, India", Nandi S et al,8 found that coverage of antenatal care services was quite high with 84% of the women having attended at least three antenatal care visits. However, the quality of antenatal care services was better in the non-tribal district compared to the two tribal districts. The proportion of institutional deliveries was lowest among the tribal (62%) and non-literate respondents (60%).Demographic factors in general favor the poor in utilizing maternal healthcare services. Age and caste of women are positively associated with full ANC, safe delivery, and postnatal care. However, the gaps in the remaining variables incorporated in the analysis disfavor the poor. Of the latter, it is the gap in the education that accounts for the bulk of the explained gap.

When Program initiatives are designed based on average performance achievements of states rather than on deprived groups, it increases disadvantages for vulnerable populations even within high achieving states.e.g.the IMR of Maharashtra9 state average is 29/1000 live births. The High performing three districts IMR is Sangli: 16 Kolhapur: 19 Chandrapur: 21 whereas, in backward and tribal districts like the IMR is Wardha: 44 Washim, Yavatmal and Bhandara: 37 Nandurbar: 36.

Can these gaps be explained by the differences in Health Literacy?

Health literacy is the term used to describe the ability to engage with health information and services. People have varying levels of education and literacy and this often influences their health literacy. Measurement approaches must be able to detect the different capacities that people have for engaging with health information and services, allowing for the fact that individuals, families and communities may develop their own effective strategies for engagement. Variations in access to health information, services and resources influence the health literacy of individuals. Where costs are high, availability is poor, or a system is complex to navigate, people require strong financial, personal and social resources to make and act on informed health choices Measurement of the health literacy strengths and limitations of communities allows strategic design and delivery of interventions that address health inequities, improve health outcomes and strengthen health systems.

If we turn our attention to inequity from birth, we find that according to the Sample Registration System conducted in 2016 in India, babies born to women in Madhya Pradesh have IMR of 47 per 1000 live births compared to those born to women in Goa, who have IMR of 8 per 1000 live births. In India, inequities with corresponding underlying axes of caste, class, gender and geographical differences define a very large segment of the population. A High-Level Expert Group appointed by the Planning Commission of India observed that considering the health inequality and social inequality interface, the poorest and most disadvantaged (the urban and rural poor, women and children, specially abled persons, and traditionally marginalized and excluded communities such as adivasis, or STs, dalits, or SCs, and ethnic and religious minorities) have a higher probability of being excluded from the health services. The infants born in these populations are expected to be the most vulnerable to morbidity and mortality.10

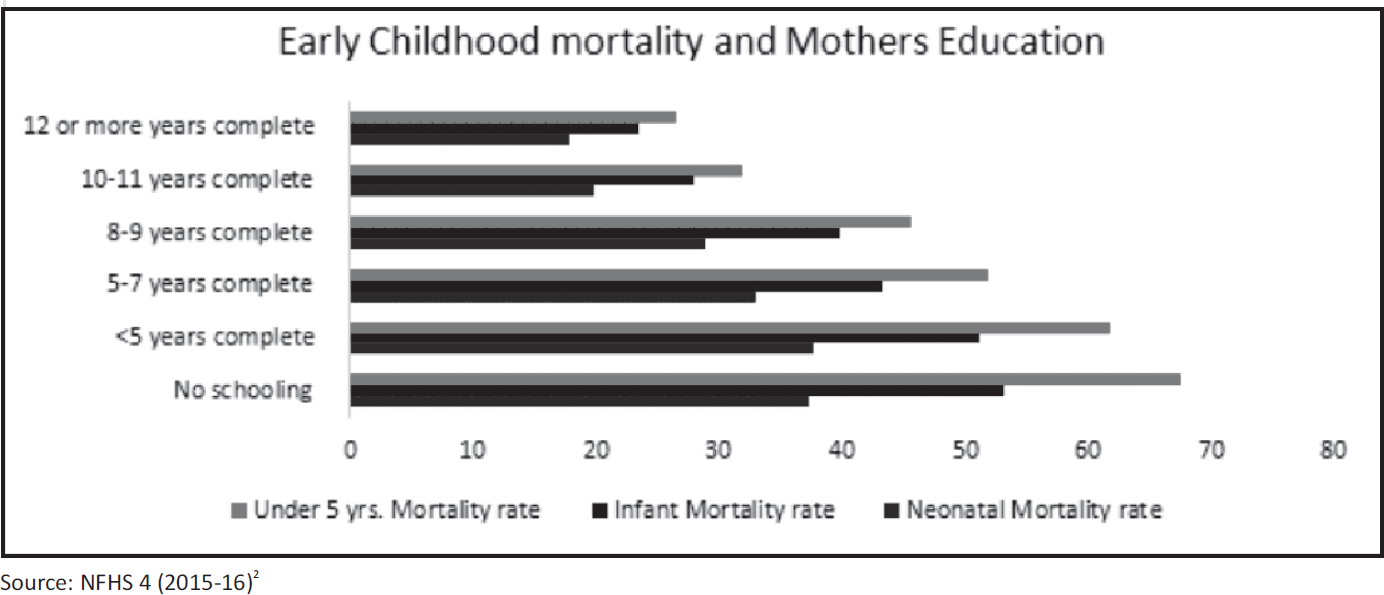

Some enigmatic revelations also exist. In a study, mortality among infants born to mothers with less than 10 years of schooling in Kerala was about 25 per 1000 live births, while it was 9.5 per 1000 live births among mothers with 10 or more years of schooling. Punjab is approximately close to Kerala in population size and rate of economic growth. The differential in infant mortality rate (IMR) in Punjab between mothers with <10 years of schooling (45.2/1000 live births) and mothers with 10 or more years of schooling (33.6/1000 live births) is 11.6, similar to the that in Kerala. Assuming that Punjab lags behind Kerala in implementation of egalitarian policies, these do not seem to have a major effect in reducing disparities in infant mortality in Kerala. However,looking at the IMR in the two states we find that IMR among mothers with <10 years education in Kerala is less than the IMR among mothers with 10 or more years education in Punjab suggesting that the influence of the egalitarian policies in Kerala, has probably led to reducing IMR and not so much in reducing "disparities in IMR", necessitating rethinking of policies & programs in education and allied sectors.

- Early childhood mortality and Mothers Education

Let us take another interesting example. Sauvaget11 and colleagues use socio-economic inequalities in mortality data from a prospective cohort study based in the peri-urban areas of Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, known for its egalitarian social policies. The study reports that low, compared to high socio-economic status (SES) groups had lower life expectancy at age 40 (about 1.5 to 2 years less). The study also found that SES disparities were wider among men than women. Social stratification thus determines differential access to and utilization of health care, with consequent inequitable promotion of health and well-being, disease prevention, and illness recovery and survival.

Poor and unequal living conditions are the consequence of poor social policies and programs. Inequity in living conditions persists from early childhood through schooling, employment, working conditions and the environment in which people reside. Depending on these conditions, different groups have different experiences, resources, psychosocial support, and behavioral options, which make them more or less vulnerable to poor health. Early child development (ECD) (defined as prenatal development to eight years of age) - including the physical, social/emotional, and language/cognitive domains - has a determining influence on subsequent life chances and health through skills development, education, and occupational opportunities. Through these mechanisms, and directly, early childhood influences subsequent risk of obesity, malnutrition, mental health problems, heart disease, and criminality. Early environments are powerful determinants of how well children develop and hence can also influence their long-term health including prevention of NCDs. Inequities in the quality of the environment in which a young child is born, lives and grows affect subsequent development of NCDs through multiple pathways. For example, evidence from cortisol measurement studies shows that children of mothers with higher educational status experienced lower levels of stress than children of mothers with lower levels of education. In some contexts, gender-bias may create inequities in developmental opportunities (e.g. quality of diet given to girls and their access to school). Given the layers of proximal and distal environments that will influence a child's developmental trajectory, interventions can be made at multiple levels by multiple partners. The common goal is to ensure access to optimal environments and quality services that can promote early health and nutrition, parenting capacity and equal opportunities for girls and boys. 12

In the existing NPCDCS program, emphasis is given on screening and early diagnosis among adults but a life course perspective would perhaps prevent sowing the seeds of the risk factors like diet, physical activity, tobacco use, leading to these diseases. E.g. if the processes producing propensity to obesity and insulin resistance are established early in life, then interventions in adults are likely to come too late to be very effective.

What then is the way forward?

It is thus evident, that simply numbers on social class, gender, ethnicity, education, occupation & income or their use as statistical covariates will never be able to provide future directions of restructuring policies and programs. Yet this is what is still happening in India. Future Public health studies need to look more at governance, macroeconomic policies, social policies, public policies, cultural and societal values as variates influencing health inequities and thereby health for all.

- Life course and Health risk

To address inequalities, we need to go beyond health care and place health on the agenda of policy makers in all sectors and at all levels, directing them to be aware of the health consequences of their decisions. Some steps in this direction include:

Parliament and equivalent oversight bodies adopt a goal of improving health equity through action on the social determinants of health as a measure of government performance along with increase in understanding of the social determinants of health among the general public to generate relevant demand for action.

The health sector expands its policy and programs in health promotion, disease prevention, and health care to include a social determinants of health approach, moving out of comfort-zones to work across sectors and support critical public policy dialogues and use the equity gauge to equitably allocatePublic resources.This means that educational institutions and relevant ministries make the social determinants of health a standard and compulsory part of training of medical and health professionals.

Governments at National and State levels establish a health equity surveillance system,with routine collection of data on social determinants of health and health inequity

Governments build capacity for health equity impact assessment among policy-makers and planners across government departments for "health in all policies" outlined in the Adelaide Statement on Health in All Policies almost a decade back. For this to be successful, we also need to build the evidence base of policy options and strategies; and clarify how Health acts as a resource for other sectors as below :

It is imperative to assess the comparative health consequences of policy options, create regular platforms for dialogue and problem solving with other sectors and evaluate the effectiveness of intersectoral work and integrated policy-making.

To build up this evidence on social determinants of health and health equity, including health equity intervention research, research funding bodies need to create a dedicated budget.

Only through this new lens, can we identify and report the "causes of the causes", make policy/makers accountable for equitable outcomes, create a platform for voicing concerns of the civil society and move towards the sustainable development of an equitably healthy society.

References:

- Research on social inequalities in health in India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:461-3. Available from: http://www.ijmr.org.in/text.asp?2011/133/5/461/81657

- [Google Scholar]

- National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. 2017. Available from http://rchiips.org/NFHS/NFHS-4Reports/India.pdf (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Inequity in maternal healthcare service utilization in Gujarat: analyses of district-level health survey data. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare - A Strategic Approach to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) in India. 2013 January:8.

- [Google Scholar]

- India's Conditional Cash Transfer Programme (the JSY) to Promote Institutional Birth: Is There an Association between Institutional Birth Proportion and Maternal Mortality? PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e67452. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067452

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation Of The Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram: Findings On Inequity In Access From Chhattisgarh, India. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(Suppl 1):A2-A43.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- of Maharashtra. Survey of Causes of Deaths scheme (Rural), State Bureau of Health Intelligence and Vital Statistics, Pune, Annual Report. 2009:48. available from https://mahades.maharashtra.gov.in/files/publication/unicef_rpt/chap4.pdf (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Submitted to the Planning Commission of India, GOI,, New Delhi. 2011 availbale from http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/rep_uhc0812.pdf (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Socio-economic factors & longevity in a cohort of Kerala State, India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:479-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early Child Development: A Powerful Equalizer, A Report for the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2007.

- [Google Scholar]