Translate this page into:

A Rural Community based study on Morbidity, Health care Utilization and Health Expenditure in Tarakeswar Block, Hoogly District, West Bengal

Corresponding author: Dr. Sanjoy Kumar Sadhukhan, P-703/A; Lake Town, Block-A, Kolkata - 700089. Email: sdknsanioy@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sadhukhan SK.A Rural Community based study on Morbidity, Health care Utilization and Health Expenditure in Tarakeswar Block, Hoogly District, West Bengal. J Comprehensive Health.2018; 6(2) :90-96.

Abstract

Background:

Rural community based recent study on morbidity, health care utilization and health expenditure is a rarity in India especially in West Bengal.

Objectives:

To find out the morbidity pattern, health care utilization and health expenditure in rural area of Tarakeswar block, Hoogly district, West Bengal.

Methods:

House to house survey of 720 families (total 2759 persons) from rural area of Tarakeswar block, Hoogly district, West Bengal, selected by 30 cluster sampling technique during 2013-14 with help of a predesigned pre-tested schedule by post-graduate students with one month recall.

Results:

Total 650 persons (23.6%) suffered from 728 monthly episodes (263.8/1000) of illnesses, more acute (147/1000) than chronic (117/1000), significantly more among males (279.9/1000) than females (246/1000). Major types of illnesses were Gastrointestinal (5.8%), cardiovascular (4.9%), respiratory (4.2%) and musculoskeletal (2.3%) including non-specific fevers (2.6%). These were primarily managed by government facilities (71.5%) and govt. doctors (66.1%) of allopathic system (93.4%). Total health expenditure (out of pocket) was 3.1% of their income, with INR 211.3 per acute illness episode and INR 84.6 per chronic illness episode. Treatment was major component both for acute (62%) and chronic (83%) illness expenditures; however, wage loss was considerable for acute illnesses (27%). These expenditures were significantly associated with social class and education (p=0.000...). Health insurance was practically nil (0.51%).

Conclusions:

There was considerable morbidity and out of pocket expenditure on health by study population. Proper implementation of any health insurance is absolutely essential.

Keywords

Rural Community

Morbidity

Health care utilization

Health expenditure

West Bengal.

Introduction:

Information on morbidity pattern, utilization of existing health care services and health expenditure are essential to plan and implement optimum health care to the community. As such, majority of the available recent studies on morbidity in India are institution based with very few community based studies on actual individual/family health expenditure of the people. Most expenditure statements are generally based on aggregate and estimated measures at national level, often in terms of GDP, GNP etc. In this regard, recent rural community based studies are a rarity in India especially in West Bengal.

With this background, present study was conducted in Tarakeswar block, Hoogly district, West Bengal with the Objectives of finding out the morbidity pattern, utilization of existing health care services and health expenditure incurred by the people residing in the rural area (having Panchayat raj institutions) of the block.

Materials and Methods:

This cross sectional community based study was carried out from May 2013 to April 2014 (data collection on Nov-Dec 2013) at rural segment (with 10 gram panchayats having a total study population/universe of 1,62,371 residing in 89 villages)[1] of Tarakeswar block, Hoogly district, West Bengal; about 56 km away from Kolkata, the state headquarter, well connected by rail and road. Sample size was calculated using standard formula (Z[2].Q/χ2.P) as per WHO guidelines [2,3] for field work where Z = Standard normal deviated at desired confidence level, P = Prevalence (Proportion) of morbidity, Q = 1-P and X = Allowable error expressed in proportion (% of P). Considering P = 0.15 (Duggal R et al[4] in Jalgaon, Maharashtra), Z = 1.96 (95% confidence), and X = 0.1 (10%), the minimum sample size came to be 2177, rounded off to 2180. Assuming an average rural Indian family size of 5, it came to be 436 families. Allowing a non response of 10% and a design effect of 1.5 for cluster sampling, the final sample size came to be 720 families. WHO 30 cluster sampling technique (Probability proportional to size, PPS)[2,3] was used to select the villages (clusters) with cluster sample size of 24. Finally, 24 families from each cluster were selected by simple random sampling and all members of the selected families were studied. (total 720 families with 2795 members.) For absentee members, maximum of three attempts were made with prior appointments over phone; however, in spite of best efforts, credible information were not available for 36 persons (1.3%) resulting in the final sample size to be 2759.

A predesigned pre-tested schedule was used to collect the information of each permanent resident member of a family from the head of the family or any responsiblefamily member by the investigators who were all medical graduates. It was accompanied by physical examination and record analysis as applicable and available. After prior verbal informed consent (explaining the purpose of the study with maintenance of anonymity, confidentiality, right to non response etc.), information were collected regarding Age (completed years; for under-five children, in completed months), Sex, Religion, Caste, Education (last class attended for ^7 yrs; n = 2245), Occupation (as stated by informant for ^15 yrs; n = 1848) and Family Income. Based on per capita monthly income, the study subjects were classified as having Social Class I - Vas per modified B. G. Prasad's classification for 2013.[5] Regarding morbidity, the diagnosis was decided by the interviewers (all doctors) by physical examination and available investigations reports. For acute illness (duration ^14 days), all present spells of illnesses and those occurred within last 30 days were considered. Illnesses persisting more than 3 months at a stretch were considered chronic.[6] Illnesses with in between durations (15 days-3 months) were considered acute or chronic as per the decision of the investigators considering the diagnosis (provisional or confirmed) of the disease. For health care utilization, the Place (Public/Private/NGO) and Type of service providers (Qualified govt., Qualified Pvt. & Non-qualified) were considered.

Regarding health expenditure, both Direct (doctor, hospital, drugs, lab investigations) and Indirect (transport and loss of wages of patients and other involved family members) expenditures were considered. It was also considered for Preventive services (immunization, ante-natal care etc) and Life style measures (Gym, Yoga etc.) Apart from history, suitable available documents were also corroborated. The reference period for these were one month (30 days recall) Data collected were entered in Ms-Excel to create a database. It was analyzed using suitable statistical techniques like tabulation, diagrams, proportion (%), mean, standard deviation and suitable statistical tests (t test, Anova).

Results:

Among 2759 study subjects in Tarakeswar Block, 57(2.1%) were infants, 300 (10.9%) were under fives, 82 (2.9%) were elderly [≥60 years], 563 (20.4%) were adolescents [10-19 years] and there were 492 (17.8%) eligible couples. Sex ratio was 897.5 (52.7% male & 47.3% female). Majority were Hindu (79.1%), followed by Muslim (20.9%) belonging to General caste (65.1%) followed by SC (28.4%) residing in nuclear families (69%) About 18% of the study subjects were illiterate with majority (59.1%) having education up to class IV and only 1.1% were graduate and above. Daily labour (47.3%) and farmer (26.3%) comprised the major occupations and homemaker (20.3%) was predominant among women. Service holders were very few (16, 0.9%). Social Class IV (49.2%), III (26.1%) and V (17.9%) were majority with very few class I (4, 0.2%). Only 14 persons (0.51%) had health insurance of any form with poor implementation of Rastriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) and 37 (2.0%; n=1848) persons practiced lifestyle modification activities of any form.

Morbidity patterns of the study subjects were depicted in Table 1. It shows that 327 (11.8%) persons suffered from acute illnesses with 405 episodes and 323 (11.7%) persons suffering from chronic illnesses. Overall, 650 persons (23.6%, 236 per 1000) were ill with 728 episodes (263.8/1000), more episodes for males (279.9/1000) than females (246/1000)[Z=1.98, p=0.048]. Acute illnesses comprised 55.6% of total morbidity. Major illness types were Gastro-intestinal disorders (5.8%), Cardiovascular disorders including hypertension (4.9%), Respiratory disorders (4.2%), Musculo-skeletal disorders (2.3%), Endocrine disorders (1.4%), STI & UTI (1.4%), Skin disorders (0.8%), Eye (0.7%) and ENT (0.6%) disorders. There were a good number of (71, 2.6%) non specificfever cases.

| Variables | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Duration of illness | ||

| Acute | 327 | 11.8 |

| (405 episodes) | (14. 7) | |

| Chronic | 323 | 11.7 |

| 2. Type of illness (multiple response) | ||

| a) Gastro-intestinal diseases | 161 | 5.8 |

| b) Cardiovascular diseases including hypertension | 136 | 4.9 |

| c) Respiratory diseases | 115 | 4.2 |

| d) Musculoskeletal disorders | 64 | 2.3 |

| e) Endocrine disorders | 38 | 1.4 |

| f) STI and UTI | 39 | 1.4 |

| g) Skin diseases | 21 | 0.8 |

| h) Eye disorders including cataract | 19 | 0. 7 |

| i) ENT disorders | 17 | 0. 6 |

| j) Injury & poisoning | 14 | 0. 5 |

| k) Dental diseases | 11 | 0.4 |

| l) Menstrual disorders | 09 | 0.3 |

| m) Malnutrition | 05 | 0.2 |

| n) Psychiatric disorders | 05 | 0.2 |

| o) Cancers | 03 | 0.1 |

| p) Fever (non-specific) | 71 | 2.6 |

The health care utilization pattern is presented in Table 2. It shows that 71.5% of all disease episodes were treated by Govt. facility followed by 21.7% managed by Pvt. facilities. NGO facility contributes only 2.3%. Regarding the type of service providers, majority of the episodes were managed by Govt. doctors (66.1%) but there were good contribution by Non-qualified (Non qualified practitioners & Medicine shop) persons (16.6%) and Pvt. qualified doctors (7.1%). Majority (93.4%) of the illness episodes were managed by allopathic system followed by Homeopathy (6.6%)

The health expenditure (out of pocket) pattern of the study subjects are shown in Table 3. For acute illnesses, monthly expenditure per episode was Rs. 211.3 and per person was Rs. 260.7. For chronic illnesses, it was less (Rs. 84.6). There were very few persons having spent for preventive care and lifestyle modification. The variability of the expenditures is reflected by the high values of standard deviation of expenditures. These expenditures were found to be significantly associated with Social Class [increasing expenditure for upper classes; F(anova)=1077.6, p=0.000........, all pair wise differences were significant] and Education [increasing expenditure for higher education; F(anova)=1028.9, p=0.000......, all pair wise differences were significant] Overall, the health expenditure of the study community was observed to be 3.1% of their income.

| Variables | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Type of health facility | |||

| a) Govt. facility | OPD | 427 | 58.7 |

| IPD | 93 | 12.8 | |

| b) Pvt. Facility | OPD | 147 | 20.2 |

| IPD | 09 | 1.2 | |

| c) NGO facility | OPD | 14 | 1.9 |

| IPD | 03 | 0.4 | |

| d) Self Medication | 24 | 3.3 | |

| e) No treatment | 11 | 1.5 | |

| 2. Type of service provider | |||

| a) Govt. doctor | 481 | 66.1 | |

| b) RMP (non qualified) | 67 | 9.2 | |

| b) Medicine shop | 54 | 7.4 | |

| c) Pvt. doctor (qualified) | 52 | 7.1 | |

| d) Health worker | 39 | 5.4 | |

| f) Self medication | 24 | 3.3 | |

| g) No treatment | 11 | 1.5 | |

| Type of illness/care | Expenditure / month | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Sd | |||

| 1. Acute illness: | Per episode (n=405) | 211.3 | 113.8 |

| Per sufferer (n=328) | 260.7 | 156.1 | |

| Overall (n=2759) | 31.0 | 67.2 | |

| 2. Chronic illness: | Per sufferer (n=323) | 84.6 | 65.6 |

| Overall | 11.4 | 27.6 | |

| 3. Preventive care: | Per user (n=6) | 370.2 | 207.3 |

| Overall | 0.8 | 11.6 | |

| 4. Lifestyle modification: | Per user (n=7) | 82.9 | 74.5 |

| Overall | 0.2 | 9.9 | |

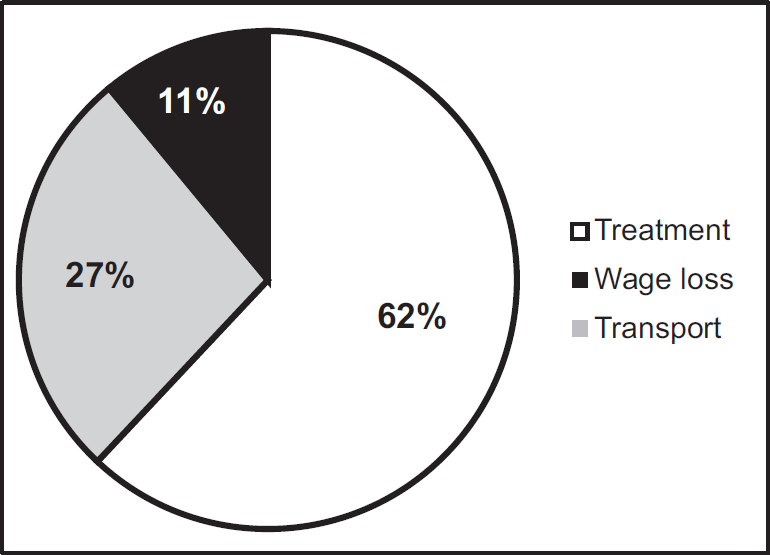

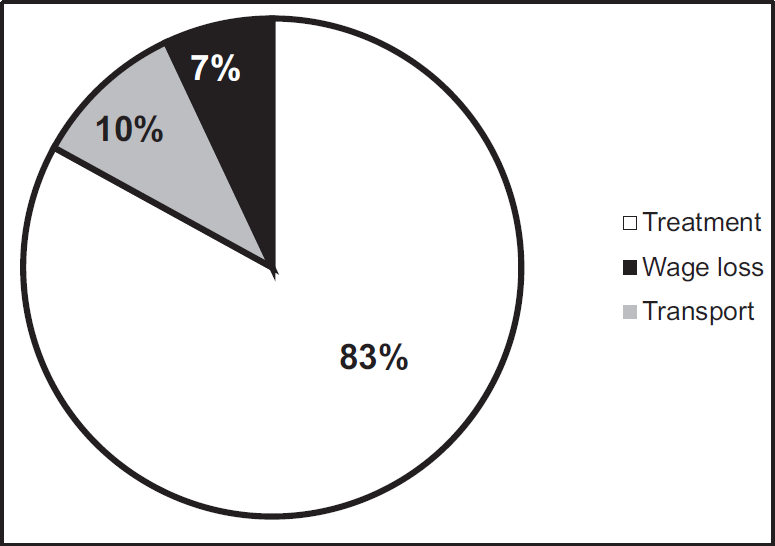

The contribution of different components of health expenditure are presented in figures 1 & 2. Treatment part is the major component both for acute (62%) and chronic (83%) illnesses; however, wage loss is considerable for acute illness (27%).

- Distribution of health expenditures in acute illness.

- Distribution of health expenditures in chronic illness.

Discussion:

In this study, Geriatric population (≥60 yrs) was found to be only 2.9%, much lower than national average of 7.9% [SRS 2011[7]] Predominance of nuclear family (69%) might be a reason. Sex Ratio in the study community was also observed to be low (898), compared to National (940) and West Bengal (947) average [Census of India, 2011][8] However, overall Literacy rate was observed to be better (82%) than that of National (74.0%) and West Bengal (77.1%) average.[9] The overall monthly morbidity prevalence in this study was observed to be about 264 per thousand. Similar figure (256/1000) was also observed by George A et. al[10] in Madhya Pradesh in 1991. Much lower prevalence (106.7/1000) was observed by Ramamani S et. all[11] in 1993 in rural India as well as by the latest (71st Round, January-June 2014) National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) report (89/1000 reported ailments)[12] A relatively higher prevalence (427/1000) was observed by Rajaratnam et. all[13] in rural Tamilnadu in 1990-91 although it was annual prevalence. Morbidity in urban India is also observed to be similar e.g. 169 (male)-571(female)/1000 in Mumbai, Maharashtra in 1994 by Nandraj S et. all[14] and 312/1000 in a slum area of Kolkata in 2014 by Kumar A. et all.[15]

Present study observed a significant (p=0.048) sex difference in morbidity prevalence [279.9 /1000 in male vs. 246 /1000 in female] Similar trend was also observed by George A et. all[10] in Madhya Pradesh but reverse trend (although not significant) was observed by Duggal R et. all[4] in Jalgaon and Rajaratnam et. all[13] in Tamilnadu. Significantly more prevalence among women (571/1000 vs 169/1000) was observed in Mumbai by Nandraj S et. all[14] No such difference was observed by Ramamani S[11] in all India study. NSS 71st Round observations[12] show more prevalence among rural women (99 vs 80/1000) These subtle differences might be due to relatively more attention to males in general and females for obstetric problems.

Acute illnesses were more observed in the present study compared to chronic one (147 & 117 per thousand respectively; 55.6% vs 44.4%). Similar proportions were observed by Kannan KP et all[16] (206.3 & 138.1/1000 respectively; 59.9% vs 40.1%) and Kunhikannan TP et. all[17] (121.9 & 115.0/1000 respectively; 51.4% vs 48.6%) both in Kerala and also by NSS 71st Round[12] for rural India (49 & 40/1000 respectively; 55.0% vs 45%) but a relatively higher proportion of acute illness was reported by Ramamani S[11] in all India study (73% vs 27%). Mean illness episode in the present study was observed to be 0.26/person and 1.01/family per month. This was observed to be 1.74/person and 6.37/family per year (=0.15/person and 0.53/family per month) by Bera T et. all[18] in at Sewagram, Maharashtra; however, their study was longitudinal in nature done about a decade earlier (2004-05) Present study observed the major illnesses as Gastro-intestinal disorders (5.8%), Cardiovascular disorders including hypertension (4.9%), Respiratory disorders (4.2%) and Fevers. Although proportion varied, similar findings were also observed by Nandraj S et. all in Mumbai,[14] Ramamani S[11] and NCEAR[19] (National Council for Applied Economic Research) in all India survey.

Regarding treatment, only 1.5% illnesses were not treated, rest 98.5% were treated. A little higher figures were obtained by NSS 71st Round (4%)[12] and NCEAR (2.9%)[19] Much higher percentages were observed by Ramamani (12%)[11] and Nandraj S et. all (32%)[14] The causes of no treatment in this study were, illness not considered serious (64%) and financial problems (36%). Nandraj S et all[14] and Ramamani[11] also reported the same.

Contrary to the findings of almost all studies, rural people of Tarakeswar Block used predominantly (71.5%) govt. health facilities for illness episodes; rest contributed by private facility (21.4%) and NGO facility (2.3%) For in-patient (admitted) episodes, this predominance was even more marked (93 out of total 105; 88.5%). All the available studies[10,11,12,13,14,15,19] reported more utilisation of private health facilities in 52-85% of illnesses including a study in a north Indian village by Ray TK et. all.(59.4%)[20] But for hospitalized illnesses, Ramamani S[11] observed a predominant use of govt. facilities. Majority of the present study subjects belonging to lower social class (Class III-V, 93.2%) in rural area with paucity of private health facility and long standing "Left" regime in West Bengal might be the reasons for such findings.

Allopathic system was observed to be the main care provider (75-90%) in most of the available studies.[11,12,13,19] Present study also observed the same (93.4%). A good number of illness episodes (67, 9.2%) in the present study were managed by Non qualified practitioners (="Quacks") and from Medicine shop (54, 7.4%), mostly by unqualified salesman. Comparable observations are lacking from most of the relevant literatures although Kumar A et all[15] observed the latter figure to be similar (7.0%) in Kolkata in 2014 and Rajaratnam R et all observed it to be 3% in rural Tamilnadu in 1990-91. In the present study, hospitalization was observed to be 3.8% of total population. Illness wise, it is 14.4% of all illnesses. Although it was observed to be lower (0.97%) by Ramamani[11] in '90s but recent ('14) NSS 71st Round[12] shows the similar figure (3.5%) Health expenditure of the study community was seen to be 3.1% of their income. Somewhat more expenditures were observed by Duggal R et. all (5.2%)[4] and Bera T et. all (4.3%).[18] Ramamani S observed it from 2.7% (for rich household) to >7% (poor household)[11] throughout the country. While comparing expenditures in actual terms, all such figures are inflation updated to the year of present study (2013-14) using the Cost Inflation Index of India.[21] Mean expenditure per EPISODE OF ILLNESS was observed to be INR 211.3 in this study which is relatively lower than that observed by Bera T et all (INR 473.4)[18] and NCEAR (INR 797.9)[19]. Mean monthly expenditure PER PERSON was INR 31.0 in this study. It was observed to be INR 40.6 by Rajaratnam J et all[13], INR 70.2 (Bera T et all)[18] and INR 29.2 (Ray TK et all).[20] From NSS 71st round (2014),[12] mean expenditure per non-hospitalized patient in rural areas were INR 509, which was observed to be INR 260.7 (overall) in this study. Relatively lower health expenditure in the present study might be due to use of govt. health facilities by the majority. Major expenditure observed in this study was contributed by treatment proper (62-83%) followed by wage loss (10-27%) and transport (7-11%). Same trend was observed by George A et all[10] in Madhya Pradesh and NSS 71st round (2014);[12] 75% and 72% respectively due to treatment itself. Health expenditure in the present study was significantly associated with per capita income (PCI) and education. Similar association with PCI was also observed by Rajaratnam J et all[13] and Kumar A et all.[15] Population of rural area of Tarakeswar block had practically no health insurance of any form (0.51%) Inadequate implementation of RSBY might be a reason for it. NSS 71st round (2014),[12] gave a better figure to be 14% for rural India, probably due to better implementation of RSBY and Kumar A et all observed it to be 22.9% in Kolkata.

Acknowledgement:

Diploma in Public Health (DPH) students of AIIH&PH, Kolkata for their sincere effort to collect data.

Conflict of Interest:

None declared

Source of support:

Nil

References:

- Block Wise Primary Census Abstract Data (PCA) - WEST BENGAL. Available from http://censusindia.gov.in/pca/cdb_pca_census/Houselisting-housing-WB.html (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies in drug utilization, methods and application. In: European series. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Publication; 1979. p. :14.

- [Google Scholar]

- How to investigate the use of medicine in consumers: WHO Regional Publication, WHO and University of Amsterdam. 2004:64-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cost of health care: A household survey in an Indian district: Foundation for Research in Community Health. presented in "HEALTH CARE: ACCESS, UTILISATION AND EXPENDITURE SELECTED ANNOTATIONS" 1989 Available from http://www.cehat.org/ publications/rhr4.html (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- An Updated Prasad's Socio Economic Status Classification for 2013. Int J Res Dev Health. 2013;1(2):26-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- SRS Statistical Report. Office of the Registrar General of India 2011:11. Available from http://cbhidghs.nic.in/writereaddata /mainlinkFile/Demographic%20Indicators-2013.pdf (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Registrar General of India. Available from http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-series/C-14.html (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Registrar General of India. Available from http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-series/C08.html (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of household health expenditure in Madhya Pradesh: Foundation for Research in Community Health, 1994. presented in "Health Care: Access, Utilisation And Expenditure Selected Annotations" Available from http://www. cehat.org/publications/rhr4.html (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Household survey of health care utilisation and expenditure: National Council for Applied Economic Research (NCAER), New Delhi, 1995. presented in "HEALTH CARE: ACCESS, UTILISATION AND EXPENDITURE SELECTED ANNOTATIONS" Available from http://www.cehat.org/publications/rhr4.html (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- NSS 71st Round. National Sample Survey Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation: Govt. of India; 2014. p. :24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity pattern, health care utilization and per capita health expenditure in a rural population of Tamil Nadu. The National Medical Journal of India. 1996;9(6):259-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women and health care in Mumbai; A study of morbidity, utilization and expenditure on health care in the households of the metropolis: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes. presented in "HEALTH CARE: ACCESS, UTILISATION AND EXPENDITURE SELECTED ANNOTATIONS" 1998 available from http:/www.cehat.org/publications/rhr4.html (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on morbidity pattern, health care utilization and health expenditure in a urban community of Kolkata: Med. Res. Chron.. 2015;2(3):353-358.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health and development in rural Kerala: A study of the linkages between socioeconomic status and health status. Trivandrum Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad 1991

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in the health status of Kerala 1987-97. Discussion paper (20) Kerala Research Program on Local Level Development, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram: p 11

- [Google Scholar]

- A Longitudinal study on Health Expenditure in a Rural Community attached to Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sewagram, Maharashtra. Indian J of Pub Health. 2012;56(1):65-68.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Household survey of medical care: NCEAR, New Delhi 1992 presented in "Health Care: Access, Utilisation And Expenditure Selected Annotations" Available from http://www.cehat.org/publications/rhr4.html (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Out of pocket expenditure on health care in a north Indian village. The National Medical Journal of India. 2002;15(5):257-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- 1981-2016-17 available at http://wealth18.com/cost-inflation-index-chart-table-1981-to-2014-for-income-tax-capital-gain-purpose/ (accessed )